Aleksandr Boldyrev sundials

Sundials and cultural artifacts

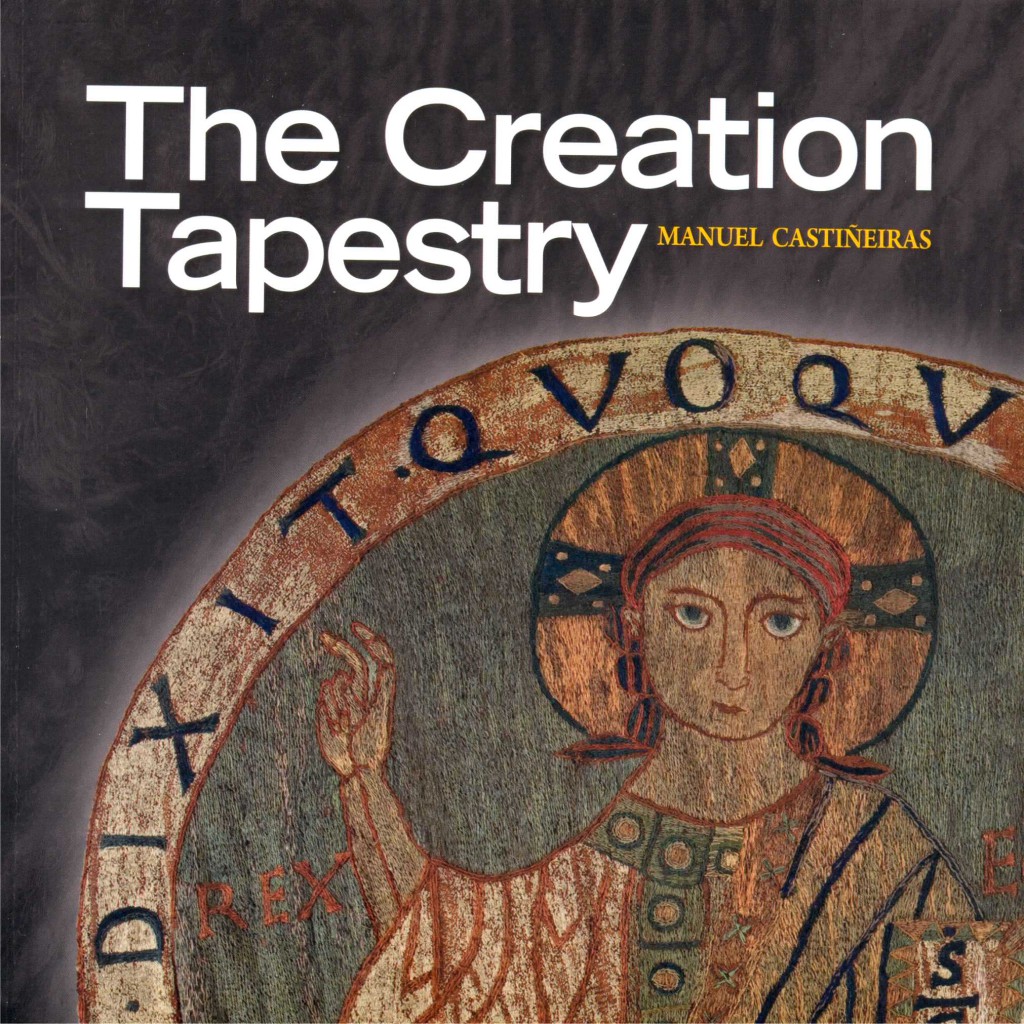

The Creation Tapestry

CONTENTS.

1. Introduction: the embroidery of Creation, an exceptional item from the Catalan Middle Ages.

2. Embroideries and wall hangings in the Middle Ages

Embroidery as a vision of the world

Embroidery as vestment

Embroidery as a feminine technique

3. The Embroidery and its iconographical programme

The Wheel of Creation and God as Cosmocrator

The border of Time and the cosmological culture of Rip oIl Abbey

The legend of the True Cross: mapping the story of salvation?

4. Function and meaning of the Embroidery

Wall hanging or Temple Veil

The Giant Carpet or Easter Carpet

Under the sign of Constantine: Bernat Umbert, the First Crusade and the young Ramon Berenguer III

5. Notes

6. Sources consulted

7. Bibliography

Manuel Castiňeiras

The Creation Tapestry

Translator Amanda Dawn Blackley.

Chapter 1. Introduction: the Creation Tapestry, an exceptional item from the Catalan Middle Ages

The Creation Tapestry, in the Cathedral of Girona, is one of the most enigmatic works of art from the European Romanesque era. In spite of the fact that the embroidery, as this work attempts to demonstrate, was most probably created for Girona Cathedral and within the city itself, neither the exact location for its production nor original function are actually known.

Furthermore, it is an exceptional item, both for its size and for the nature of an iconographical programme that is most original in combining the biblical repertoire of the Creation, the cosmography of the calendar and the history behind the legend of the True Cross. All of these elements are in turn synthesised from the knowledge of an existing solid cosmological early-medieval culture, with strong classical, Carolingian and Byzantine roots, typical of a great scriptorium, monastic or cathedral library. In the second half of the 11 th century (the most likely period that the embroidery was created) Catalunya was home to a number of important centres of teaching, study and illumination, where it would have been possible to find the models and ideas to develop the complex iconographical programme that is presented in this work. The monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll and the collegiate of Sant Feliu de Girona seem the most likely candidates, although in elaborating a cloth of such dimensions, one thing is the actual design or tracing of the iconographical programme; the work of the auctor intelledualis, and another is its reproduction on the cloth by the auctor materialis. However, it should be remembered that weaving has always been a craft requiring a great deal of time and patience and was thus typically the work of aristocratic women or nuns. It is therefore hypothetically suggested here that the embroidery may well have been created in a female monastery under the guidance of an important lady of the nobility. As will later be explained in more detail, the most likely candidates in this respect were the Benedictine nuns of Sant Daniel de Girona, who continue to silently undertake the needlework craft of liturgical ornaments to this very day. This coenobitic monastery was founded in 1018 by the Countess of Barcelona, Ermessenda (also known as a patroness of the new Romanesque Cathedral of Cirona), and by the end of the 11 th century was under the protection of Countess Mafalda from Apulia (1060 — 1112?), widow of Ram on Berenguer II and mother of the young prince Ramon Berenguer III. Mafalda is likely to have played an important role in the genesis of the Tapestry.

As far as function is concerned, a series of new technical and compositional discoveries have meant that former ideas regarding the use of the embroidery as a wall hanging or ceiling canopy have been replaced with the serious consideration of its use as a «floor tapestry» or pavement carpet. In fact in the inventories of altar furnishings for Catalan churches between the 10th and 12th centuries the cloths are designated as tapeta, tapetios or tapecios. In this specific case a suggested use would be as a decorated carpet for Easter celebrations, and for the feasts of the Invention and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Chronologically speaking it seems that the most likely year for it to have been triumphantly mounted in Girona Cathedral was in the year 1097. The cloth may well have been used as a luxury carpet for the 1097 council presided over by the Papal legate and archbishop of Toledo, Bernard de Sedirac, a meeting intended to resolve the internal conflicts of the Catalan church, affirm the power of the young count Ramon Berenguer III under protection from the Holy See, and to encourage the definitive restoration of the metropolitan see ofTarragona. The iconographical programme of the embroidery actually reflects a number of these concerns.

The most noteworthy feature of the nominal Creation Tapestry, conserved in Girona Cathedral's Treasury, is its sheer scale, and the fact that it is actually just a fragment of a larger whole (fig. 1). In spite of the embroidery's considerable size (358 x 450 cm), what survives is in fact just one part of the original that has been conserved. According to the recent technical studies made by Carmen Masdeu and Luz Morata, evidence seems to indicate that the piece was originally much longer and wider. In its current state the embroidery is made up of six rectangular, similar bands of fabric. The upper-most band is the only piece that has been conserved almost entirely and provides us with information relating to the length of the loom that produced the six strips: 420 cm. However this particular band has the unique feature of having been placed horizontally whilst the other five are situated vertically, and are all cut at the bottom, measuring only 293.5 cm, with the width of the piece laying the furthest to the right particularly reduced. Although all the strips have different widths, the length seems to have been the same, meaning that it is possible to deduce the original size of the embroidery from the upper border (originally measuring 420 cm), that leads us to assume that the vertical strips, that now measure 293.5 cm, were originally 12S cm longer at their lower edge. There would also have been an additional section that is missing along the right-hand border, which from comparison with the left-hand band and the composition of its scenes, would have measured 60 cm across. It can therefore be deduced that the embroidery would have actually measured 480 x 480 cm; a size that would have encompassed the complete representation of the calendar on the side borders, with the February and January scenes on the left, November and December on the right. Finally, upon study of the composition of the iconographical programme and the actual structure of the cloth, there is further evidence to prove an additional missing lower band measuring 60 x 420 cm, that would have been placed horizontally to strengthen the structure whilst completing the figurative cycle of the two rivers of Paradise; Tigris and Euphrates, and the missing five days of the week. Likewise there were also another two scenes that will be outlined further in this study.

Thus the original measurement of the embroidery would have been 480 x 540 cm, or a third longer than its current state, with the complete embroidery being made up of seven bands of fabric of the same length; five placed vertically and two horizontally, with an additional two smaller pieces that would have been situated in the upper and lower right hand corners. In fact, as well as being possible to clearly distinguish the stitches that joined each of the bands, this reconstruction also gives an explanation for the poor state of the vertical right-hand side, that was as previously mentioned originally composed of three different-sized fragments; a small cloth in the upper corner (of which some fragments still remain), that was joined to another with the same length as the other vertical bands (420 cm), and a third, now absent that was lower down and smaller. This was in fact the most fragile part of the whole piece and when the Tapestry was actually found at the end of the 19th century, the pieces had already been separated and were not correctly reintegrated until its restoration in 1952.

From a technical point of view, the embroidery is unique in that it is made on a red chevron of fine wool, with a strong twist in the «z» and a weft: in the "s': The woolen chevron is embroidered with woolen thread and bleached linen fiber on a long needle, following a longitudinal direction, namely, towards the warp of the loom, with the particular characteristic that in the upper band the cloth has been arranged horizontally. The technique used is for acu pictae fabric, or needlework painting, where the black thread is used to outline the figures and separate the colours as was the case in mural painting. Likewise, although the background and interior of the figures, that are characterised by large patches of colour, are made with a stem stitch that resembles a paint brush the outlines of the figures, such as the hair, bodies and landscape for example, are distinguished by the use of a thicker cord stitch.

The colours are very varied, lively and contrasted, with a predominant use of green, yellow, red, burnt earthy colours, blue and white. The aforementioned colour black was used for outlining the figure, whilst the other colours brought them to life and added composition to the background. The cardinal winds' wineskins are depicted in yellow tones, the scenes of genesis a burnt earthy colour, the cycle dedicated to the Invention of the Cross is made up of intense greens, dark blues on a red-purple background, and finally the inscription signs are in white with letters in yellow, blue and pink. The result is quite extraordinary and denotes great skill and technical command.

Until now no conclusion has been reached for the singular feature that the work is embroidered on a woolen chevron and not, as in other contemporary examples, on fine silk, as with Henry II's cloak, or on linen, as is the case for the famous Bayeux Tapestry. In the case of the latter, created as a fabric wall hanging, the material is actually linen twill, made up of nine strips and embroidered in wool and linen. Silk and linen are both materials that give cloth a great deal of flexibility and lightness, which is certainly not the case for our woolen Tapestry that is thicker, heavier and not at all flexible. In fact its very material characteristics are closer to those of a woollen oriental carpet, made on a vertical loom, with a resistant, inflexible woolen warp, and a framework of the same material. Originating in the Middle East, Persia and Babylonia, as floor decoration for courtrooms, they were very widespread in the Coptic world, as woollen taquetes to be used as tabulae, and were particularly abundant in Turkish Anatolia with the production of Konya carpets from the 11 th century onwards representing the symbolism of Heaven, Paradise and the Creation of the Earth in different shapes and colours. Curiously, the first place in Europe where this technique was found from the 11 th century onwards was Muslim Spain. In Murcia, Chinchilla (Albacete) and Cuenca, it most likely arrived from the Coptic world of Fatimid Egypt. In fact, in his Description of Africa and Spain, Al-Idrissi refers to these excellent quality woolen tapestries with marvellous tones of red and green. As will be outlined later in this study, the original function of the Tapestry as a tapetium could well have its origins in knowledge of the Andalusian examples.

The term «Tapestry» has been chosen for reference throughout this study. Although from a technical point of view the Girona work is not actually a «tapestry» and is in fact «embroidery», the use of italics indicates that it is the name that has been adopted to refer to the piece since its discovery. Whichever the case, the word responds perfectly to the generic use adopted in the Middle Ages, where «tapestry» was used to denominate any type of embroidered hanging. In fact even today in English and French literature the terms tapestry or tapisserie are often used generically.

The first documented reference of Girona Cathedral's Tapestry was actually quite late and dates from the visit from Emperor Charles V to Girona on 25th and 26th February 1538. There are two recordings for the monarch's stay in the city: the first is registered in Girona Cathedral's records, and explains how he visited the see and attended mass in the presbytery, where he was shown the altar treasuries, and in particular, a goblet that according to ancient tradition had belonged to Charlemagne. The second reference that is conserved in the Girona Municipal Archive, explains that once mass had finished, and he had seen the jewels and had lunch, «torna en dita yglesia y volgue veure 10 Drap de Carlesgran de la historia del emperador Constanti» (he returned to the church and asked to see the Cloth of Charlemagne showing the history of the Emperor Constantine), before going to Sant Feliu to see the body of Saint Narcissus. A comparison of the two records is interesting, since it is clear that after mass on Tuesday, 26th February, Charles V saw the altar treasury conserved in the Cathedral's main chapel, but only in the second record is it specified that he returned there with the sole purpose of seeing the Cloth of Charlemagne depicting the history of the Emperor Constantine. It can thus be deduced that the fabric was kept in a different location and a certain delay was necessary to attend to his request. As Lluis Batlle suggested, the evidence seems to indicate that the cloth in question was quite probably the Creation Tapestry, likely to have then still been complete including the bottom strip with the portrait of Constantine and the Cross, surrounded by the cycle dedicated to the discovery of the True Cross. The size of the cloth would have meant that it was more than likely kept in the sacristy or treasury since it was not normally on display to an audience and more than one person was required for its transport.

The frequent references to Charlemagne are unsurprising. In Girona legend relates the freedom of the city and the foundation of the cathedral itself to the Carolingian Emperor. Secondly the cult of Charlemagne, a cult that developed notably in the 14th and 15th centuries increased the monarch's power through such objects. When reference is made to the Romanesque seat and tower these are actually called «Charlemagne's», including the aforementioned «Charlemagne goblet» that first appears by this name in the Cathedral's documentary records in 1538. This last item, mentioned in the 1470 inventory, was located in a box belonging to the treasury, and disappeared during the 19th century. However it is described in great detail in the Inventario de la Tesoreria de Pere R...ossello (inventory of the treasury of Pere Rossello) in 1695, where mention is made of the ‘Charlemagne goblet or cup’ «de plata sobredorada, ab la figura de Carlos a cavall y alguns gossets, dintre al mig de dita copa ab 10 cubertor que al remate te tres figuras al mig y una al capdemont» (made of gilt silver featuring the figure of Charles on horseback, and some little dogs, whilst the inside of the cup, its lid and top had three figures in the middle and one above.). The same record seemingly alludes a second time to the Creation Tapestry, with the reference to «colgaduras de drap de rasos per adornar la Iglesia» (a wall hanging drape for decoration of the church) and the mention of several cloths that depict the history of the Prodigal Son, the counts of Barcelona, of David and «altre pessa dita de Constantino» (another of Constantine's spoken items).

Whatever the case it is clear that at the end of the 19th century any memory or use of the embroidery had practically disappeared. Curiously we owe its rediscovery and restoration of value to the work of a scholar from Granada, Juan Facundo Riafio y Montero (1829—1901), Professor of Fine Arts at the Madrid Escuela Superior Diplornatica from 1863 and a director from 1870 at the South Kensington Museum in London for the acquistion of Spanish antiquities. In 1872 Riano made a catalogue of Spanish objects for the museum and a few years later in 1879, published a monograph in London written in English as part of the South Kensington Art Books series titled Spanish Industrial Arts, where one of the first reproductions and commentaries of the Girona Embroidery can be found. In fact, it is clear from the references made by the academic and native of Girona, Enric Claudi Girbal, a chronicler for the city, curator for Girona's Provincial Museum (opened to the public in 1870 within the monastery of Sant Pere de Galligants) and Vice President of the Girona Monuments Commission, that there was discussion among French scholars regarding the possibility of sending the Tapestry to Paris for the Universal Exhibition in 1878. This leads us to believe that the work was rediscovered at some time between 1874; the year the 1470 inventory was published by Fidel Fita, where as yet no reference was made to the Tapestry, and 1878, when the piece was already known among Parisians from the photos sent by Enric C. Girbal. In that same year, the academic and native of Girona had published his first study of the work in a Madrid publication La Academia with a watercolour illustration that was used the following year by Riaňo. Girbal went on to re-publish his first study with new findings in the Revista de Gerona (1884). According to the aforementioned author, the first restoration and exhibition of the Tapestry was thanks to the Dean of the Chapter Josep Sagales i Guixer who rescued the work from oblivion. The work quickly became famous and was exhibited firstly in the archeological section of Barcelona's Universal Exhibition in 1888, where its loan is documented in the Cathedral records (23rd February 1888, p.513) as a «Byzantine tapestry» and later in Madrid for the Historical-European Exhibition held in the year 1892.

As is the case for both catalogues as well as the publications made by Riaňo (1879) or Lluis Domenech i Montaner (1897), the work is presented in a more fragmented state than today; missing the figure of the labourer in the month of April and the entire righthand border. Although Girbal had already explained in 1884 that this fragment had been found «among some old cloths» and that it corresponded to the right hand side of the work, when the second restoration of the Tapiz was undertaken at the beginning of the 20th century, possibly for the Barcelona Antique Art Exhibition (1902), this fragment was inexplicably sewn to the lower edge of the embroidery by «specialist» French nuns. A third restoration was undertaken on 12th May 1952 for the remodelling work to convert the Chapter rooms into a museum, with a budget of 5000 pesetas. We know that this initiative came from Monsignor Llambert Font with the counsel of Art Historian ]osep Gudiol i Ricart, and that the operation mainly consisted in situating the right-hand band in its place, laying the work onto a light brown material and framing it behind glass. Finally on 11 th September the same year an agreement was made in the Chapter that the piece would never again be moved or loaned. Later in the 1970s there was once again intervention from Father Genis Baltrons when another fragment that showed the representation of some kind of architectural structure was found «behind one of the Cathedral tapestries, that was covering a hole».

Both the fragment in question and the whole embroidery were sent to be cleaned and discussion began regarding a fourth restoration. As documented in the Cathedral records (Actes Capitulars, 2nd January 1973 and 1 st February 1974), the most suitable candidates for this task were the Benedictine nuns of Sant Daniel, since they had the «means, technique and potential to do so correctly». Yet the work was finally undertaken by the Adorer Sisters of Girona, with less than successful results. As outlined in the report made by Carmen Masdeu and Luz Morata the intervention involved adding the newly-found fragment, the unfortunate reintegration of all the gaps in the fabric, and the bold reconstruction of the Pantocrator’s face and the month of April figure.

However the interest shown in restoring the work on two different occasions in the third quarter of the 20th century is proof of the great attention and fame the piece had acquired both within and beyond Catalunya. It is not by chance that each of these interventions coincided with the impetus and studies of archeologist and native of Girona, Pere de Palol (1922—2006), who was Professor at the University of Barcelona and possibly the greatest expert and specialist on the work. The studies in question refer to the series of articles published in the prestigous Spanish magazine Goya in 1955 and the French publication Cahiers Archeologiques in 1956 and 1957, that have since provided academics with the main clues to understanding the iconography of the work and particularly the monographic book published in 1986 as part of the Artestudi collection; today still an important reference text on the Tapestry. As recorded in the Cathedral of Girona's Actes Capitulars. Pere de Palol began working on this text as early as 1973.

The book can be purchased at the Cathedral of Girona